Bowden Contra Bowden

Bowdenpilled: Jonathan Bowden as a Philosopher

What is Truth? — Pontius Pilate, The Gospel of John, 18:38

No people was ever saved by dumb preachers. — V.L. Parrington, Main Currents in American Thought, Vol. 3, p. 127

Socrates: Shall we set down astronomy as a third, or do you dissent?

Glaucon: I certainly agree, for quickness of perception about the seasons and the courses of the months and the years is serviceable, not only to agriculture and navigation, but still more to the military art.

Socrates: I am amused at your apparent fear lest the multitude may suppose you to be recommending useless studies. — Plato, Republic, Book VII

Does truth matter? Pilate’s handwashing symbolizes the triumph of expediency over principle. The axiology of truth is not only a fundamental question of Western philosophy but also a core aspect of the West's overlapping religious, ethnic, national, and racial identities.

Jonathan Bowden (1962-2012), a britbong with varied interests spread too thinly, wasn’t a great or even a good philosopher. His worldview merits exploration for two reasons. One, his Nietzscheanism recently reoriented Anglosphere conservatism, which had a skeptical mentality for decades, toward a heroic (or, some critics would say, willfully blind) outlook. Secondly, Nietzschean indifference to truth is a general feature of the Second Gilded Age and deserves examination in its own right. We’ll also pursue several lines of critique, especially questions of product differentiation. We’ll ask if Bowden’s politics has any daylight with vanilla conservatism, if his right-Hegelianism has the resources to reply effectively to the Frankfurt School, and whether his Nietzscheanism can situate itself in a world brimming with other Nietzscheans, specifically postmodern poststructuralists and identity theorists. I’ll even include excerpts from my last interview with him. But first, a prelude before we start thinking about Satan worship, which is the cash value of Bowden’s deliberately vulgar philosophy, which I hope to demonstrate critically is a period piece more than an original vision.

Prelude

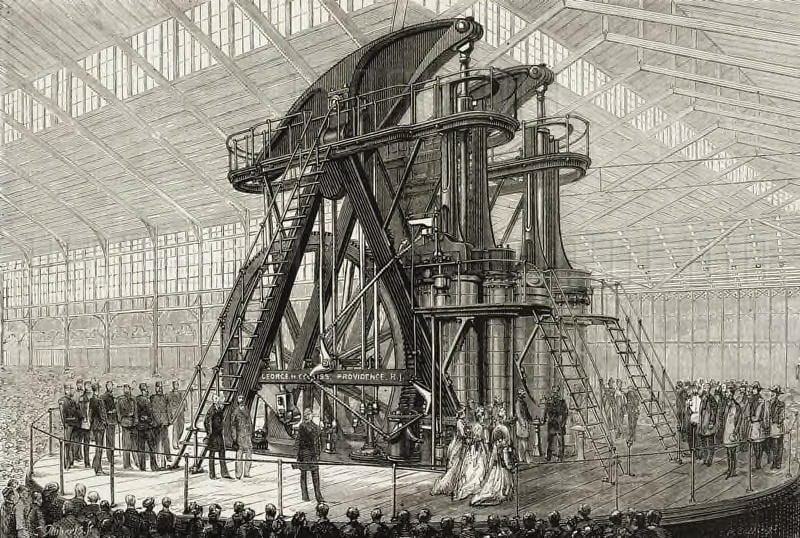

”I’ll be damned.” A confused and turbulent scramble. Like Paul of Tarsus, many a Gilded Age man knew the better but chose the worse. Railroads. Gas. Steel. Heavy industry. Corporate finance. Copper. Lumber. Gold. Silver. A big bang of industrial expansion. Amalgamation and Capital: consolidatory, centripetal energies. The machine order, conspicuous by its novelty. Pioneers of rigor and professionalism in an orgy of self-seeking, corruption, predation, exploitation, single-mindedness, ruthlessness, inequality, religious cranks, economic cranks, political cranks, moralizing cranks, cranks, cranks, cranks. A scramble for life; heedless, irreverent, huge beards; a triumph of unabashed vulgarity. Brahms, trolling by writing high, technically spotless academic music based upon student drinking songs. Parroted platitudes; changeable convictions unscrupulously determined by social position. Raw people with raw origins seeking raw advancement and raw success. Ulysses S. Grant (now rehabilitated in the sequel). P.T Barnum: Trump before Trump. Stuff, stuff, stuff, stuff, stuff, stuffed with stuff. Materialism, possessions, riches, abundance, acquisitiveness, squandering, conspicuous consumption, indiscrimately more, more, more, more! Architecture, like the postmodern McMansions of today, overloaded with meaningless and incoherent detail to tastelessly provide the feeling of value. Collect them all: an eclectic quest for ready-made, disposable historical styles and identities.

Life, no longer an aristocratic contest between men, but a struggle between primordial forces.

Academicism: the relentlessly imperialistic drive, from the sciences to the humanities, to make contact with universal, formal truths independent of time and space. Orientalism: another endeavor to overcome the particularity and individuality of realism to reach the other-in-time and other-in-space. Imaginary, legendary, genre-like landscapes, everything in the scale of Ecclesiastes, an obliteration of the temporal through universal experience. The individual surrenders to All: gaudiness, sensuality, gore, opulence, collectivism, magic. Lost: distinction, dignity, refinement, grace, harmony, craftsmanship, manners, balance.

And what of religion? Suffering, once an immutable fact of life, could now, at least in principle, be ameliorated. Holding out hope for Christianity in some rarified and secular sense, Gilded Age thinkers sought the unification of appearance into a supersensible unified reality. Religious or not, all felt the loss of Christian gravity, even as religion persisted among the middle classes as another cheap product. This long list includes Henry Sidgwick (1838-1900), Henry Adams (1838-1918), William James (1842-1910), etc., etc. etc., and yes, it includes Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900).

Now, I send you back to the future so that we may begin.

The Philosophy of Jonathan Bowden

Is there more to life than shopping? Is the career path the only path? Are you even alive? For Jonathan Bowden, extremism tells a story of rebirth. Radicals create new categories of action (we can’t deliberately do something until we know what we are doing), function as early adopters for emerging trends, and serve as a vanguard for those who instinctively understand affairs but lack the concepts to articulate their perspectives systematically. Like Maurice Cowling, who considered J.S. Mill a “moral totalitarian,” Bowden views liberalism not as something nice, tolerant, and inclusive but as a hegemonic, devouring, and standardizing viewpoint that punishes non-elective identities. Given there are other forms of life, both fictionalized and real, from the Byronic license of Gabriele D’Annunzio to the ascetic warriorship of Yukio Mishima, why live merely, as corporations call it, a human resource?

Bowden has a villain: Anglosphere conservatism. With religion lost, conservatism deliberately tells universalist and individualist myths as noble lies; it has a materialistic, anti-intellectual, and pessimistic core. It still unconsciously participates in time in Christian (and ultimately Judaic) terms as linear and unidirectional; the present gains meaning only through what occurs in the future. Expressed differently, conservatism looks at the cosmos and finds existential persons inhabiting a scientific world filled with uniform dead stuff; ultimate reality is fundamentally Other, like the Abrahamic God. This resolves life, even the relationship between the philosopher and the non-philosopher, into a disenchanted series of compromises; we prudently take what we can get from the system through voting and purchasing decisions. This can be rationalized as a slow retreat to a safe, gentle, comfortable defeat, but that’s not what happens. Rational self-interest — the path of least resistance — leads to paralysis when facing global changes almost Biblical in scope, thus making the conservative a patient rather than an agent of history.

What does literature — always more real than life — say about the interplay between civilization and radicalism? In a scene from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Settembrini (a big-brained centrist who advocates liberal humanism) and Naphta (a mystical, Evolian fascist fanatic) enter a duel. Settembrini, sticking to his pacifist principles, fires into the air. Naphta responds by absurdly shooting himself in the head. Like Kirillov in Dostoevsky’s novel Demons, Mann suggests edginess, non-conformity, and transgression, while proving freedom, paradoxically have self-destruction at their ground. Master morality becomes a slave morality; self-ownership becomes a self-own.

Bowden, who enjoyed thinkers advocating metaphysical idealism — sometimes with a pagan flavor, sometimes with a Christian flavor, sometimes both — attempted to break this game by changing the metaphysical perspective. He was like a photographic negative of postmodernity, sharing the same distrust of rationality, individualism, and progress, reckoning everything as conditioned, pushing relativism to its transcendental extremities until it became radically essentialist. Why can’t texts be deconstructed to reveal truths deeper than their surface — the pattern, the essence, the archetype — instead of absence? What principle internal to postmodernism prevents this? If all is narrative, why not be indifferent to the crimes of history? If everything is intersectional, that is, interconnected, doesn’t this have the idealist consequence that everything that exists is divine? This would give license to partiality, to exclusivity, to militancy, to Thomas Carlyle’s conviction that conviction itself moves the world. Leadership then assumes a divine nature, as the revelatory import of belief has more perspectival significance than obeisance to statistical averages. It follows that, like Joseph de Maistre, the irrational invigorates; the rational vitiates. And, taking a cue from Charles Maurras, Bowden rejected the sovereignty of the individual; someone can be guilty for connective and social-organic reasons — think of Quintesson judges from Transformers’ lore — just as Maistre felt Christ on the cross lays down a metaphysical law that the sins of the guilty must be paid by the sacrifice of the innocent. Idealism even allows us to reject the primacy of space and time, thereby resurrecting formal-final causation and other teleological thinking. If the universe is for us at some fundamental level, we can think of the evolutionary process backward, as if apes are descended from us.

Themes

Jonathan Bowden’s philosophy is not a set of ideas but a set of themes.

Bowden had strong tastes and believed truth is deeper than reason. Like most conservatives, he preferred sublimity over beauty. A man of extremes! He loved thresholds of every variety, eschewing professionalization, analysis, and fact. Bowden was not remotely mechanistic. Nor was he skeptical. He disliked education, balance, refinement, prudentiality, obligations, and responsibilities. Typical for a conservative, he had a shipwrecked mindset. Apocalyptic aesthetics; apocalyptic scenarios. Western civilization is supposedly facing extinction, and Bowden was here to save it! Modernity feels unheroic and mediocre; it needs an injection of greatness. This is not a new mentality. It goes back to Edmund Burke (1729-1797), yes, Edmund Burke, not his political theory, but his aesthetics. Burke decoupled the sublime from the beautiful as an independent aesthetic category. In 1757, he was overwhelmed with apprehension that the world was becoming gray and colorless and filling up with non-playable characters (NPCs).

Like Nietzsche, Bowden believed everything is Heraclitean fire or energy. He believed in becoming. He believed in dynamism. He believed creation and destruction go together. This was his primitivism, his vitalism, his naturalistic rejection of the dualism of good and evil. Nietzsche’s philosophy served as a substitute heretical religion, a paganism ferociously celebrating the sacredness of life. Some, born with the right stuff and with high energy, burn brightly. Some do not. Bowden believed life is its justification; self-affirmation is what it is. The power of this suite of ideas comes down to whether we are alive and whether we know whether our lives have been worth anything.

Bowden was deeply personalist and subjectivist. He demanded nothing less than a total commitment to a total view of the world. Outer reality seemed to only exist in the Fichtean sense of that which thwarts our will. Bowden understood (or misunderstood) modernism as based upon mental interiority; he put confidence in art's metaphysical significance and held that technological sophistication left art with no other place to go. Humans are not the same underneath; we do not dream the same dream. Bowden also placed trust in Greek tragedy, like horror, for the way it interiorized negative emotions and then purged them through sublimation. This reverberated strongly with his Eurocentrism. Bowden believed the West, its art, its literature, is inherently perspectival, inherently partial, inherently individual. History is about us, or it is nothing.

Newly opened vistas of human experience, consciousness pushed to its limits. Transcendence, the other-worldly, the diabolical. Unconscious ideas, fantasies, desires, imaginative forays. Iconic art, religious paintings, the occult, spiritualism, pornography, the insane. The heretical, the blasphemous, the evil, the degenerate. Bowden wanted to live on terra incognita. He wanted the radically different, in principle. Anti-humanism, vanguardism, misanthropy, offensiveness. Intensely hating the prosaic, Bowden believed the world, even in the best of circumstances, can only go so far in telling us what life is about. At some point, we must discriminate; at some point, we must make a choice. And at some point, we must leap over the present. Bowden was not an enemy of suffering. He was, however, an enemy of meaninglessness.

What are you willing to live for? What are you willing to die for? What are you willing to murder for? Bowden’s volcanic worldview celebrates competition: that which is aggressive, domineering, incendiary, strenuous, combative, disagreeable, arbitrary, warlike, powerful, rugged, proud, biased. Competition theatrically creates winners and losers, heroes and villains, at every level of life, which in turn establishes inequality and hierarchy. This is the neo-Romantic, right-Hegelian dogmatic motor of everything else he does, i.e., the slaughter bench history evolving as the dialectical conflict between competing convictions.

Bowden’s dogmatic view is similar to that of conservatives who lived through the Napoleonic era. Any theorist of history, especially if they are a rationalist or a moralist, must explain rare, unpredictable events when irrationality erupts and pours over the world, times when leaders such as Napoleon or Mohammed inspire thousands and thousands of men with frenzied conviction to reconfigure much of human life on the planet. Mechanists may mention factors such as immiseration, elite overproduction, demographic balance, etc. An organicist may speculate about the morphological life-cycle of a civilization. But Bowden’s doxastically-powered frame of mind implies an aristocracy should contain winners who emerge through the laws of development and creative evolution of a society; failure to do so, perhaps by men without merit, parasitic on the successes of one’s predecessors, loses the Mandate of Heaven and invites the judgment of God. These are poetic expressions of prestige that cannot be analytically quantified.

The Final Interview

JB: Thank you, Mr. Bowden, for coming back from the dead to talk with us. You’ve really gone above and beyond.

JB: …maaaargh

JB: Um, ok. To begin on a light topic, the earliest known Bowden in my line, John Bowden, came to the United States in 1818. Do you think there is any chance we’re distant relations?

JB: …maaaargh

JB: Sir, you’re drooling.

JB: …bhrrains …BRAINSHS!!!

JB: oh shit

Heroic Conservatism

At first glance, Bowden’s philosophy contradicts modern conservatism. Philosophically, conservatism not only has a prudentialist, pragmatist, Burkean aspect, but also a skeptical component extending to men such as Michel de Montaigne, George Santayana, and someone like John Gray in the present. Even the doxastic and belief/faith-based ideas of Counter-Enlightenment men such as F.H. Jacobi and J.G. Hamann have roots in David Hume — the skeptical conservative gives the dogmatic conservative permission to shrug at philosophy. If our brains malfunction, philosophy can't help us; when everything behaves naturally, we don't need philosophy. This is a steady-state theory of human nature. Its enemy is what H.L. Mencken labeled as "the uplift." If the future fundamentally resembles the past, then revolutionary activity from what Thomas Hobbes called the "democraticals" should be repressed by sober authorities as an enthusiastic threat to public order. These trends came together with modern conservatism, a product of men such as Michael Polanyi (1891-1976), Karl Popper (1902-1994), and Friedrich von Hayek (1899-1992). Here, at a first approximation, individual knowledge is fragmented and limited. What is handed to us from the past is given the benefit of the doubt as beliefs, traditions, practices, and, yes, dogmas that have been battle-tested over time. Decisions about the future are made in a pragmatist, tentative, prudential spirit that clarifies and respects trade-offs and time constraints. This philosophical recipe was the backbone of the most successful Counter-Revolutionary effort in history — the rollback and eradication of communism.

Is Bowden's heroic dogmatism really at variance with this suite of ideas now consolidated in Thomas Sowell's writings? Carl Menger, one of the founders of marginalist economics, was a value subjectivist, an idea built into the contemporary mode of economic reasoning. It is a small jump to this to Bowden's hero, Nietzsche, the philosopher of reaction par excellence, the Gilded Age man who replaced talk of virtues with values, a time when what was once believed to be certain, eternal, and invariant was now up for grabs and felt its persistence into the future depended upon volition. Nietzsche's disdain for metaphysics isn't unique; that work was done by the early moderns influenced by skepticism, such as Montaigne, Gassendi, and Bayle. Speculative metaphysics came back during Romanticism, but by Nietzsche's time, critical neo-Kantianism dominated the philosophical scene in Germany. Nor is Nietzsche's Lebensphilosophie unique; other men of the Gilded Age, such as Simmel, Dilthey, and James, attempted to push philosophy into the same current. Nietzsche's uniqueness consists in his willfulness, specifically, the egotism that Santayana viewed so essential to Germanic philosophy.

Boomers feel 1945 and the fall of the Third Reich as a historical anchor. But no one asks about the Second Reich or even the First. Germany was the land of Reactionary Modernism, stepped down from heaven into the world, and made flesh, incarnated in the form of a nation-state. Germany was once the Holy Roman Empire, but this political structure became increasingly impotent by the 1700s. In the War of Austrian Succession, Prussia, the new, progressive, modernist, enlightened, future-oriented country, invaded Silesia. In response, many German princes prioritized their interests over their loyalty to the Habsburgs, including Bavaria and Saxony. Maria Theresa had to rely upon non-German allies like Britain, the Dutch Republic, and Hungary to maintain her position. Charles VII was briefly crowned emperor (1742-1745) and it meant nothing. The Empire appeared to have lost the ability to respond creatively to history. Nietzsche, Janus-faced like every good conservative, wanted both the Holy Roman Empire and Prussia at once, a Germany that wasn't a petty nation-state but fully returned to the imperial status to which Germany had been accustomed for centuries. Nietzsche admired Prussia's strength, discipline, and organizational clarity, but he didn't like its narrow nationalism and middle-class values. And with the Holy Roman Empire, he saw a lost opportunity for a grand, pan-European aristocratic culture -- a metaphysical hypostatization of the Gilded Age, the highest high-life, complete with a full, pagan rejection of Christianity, weakness, and petty local politics.

Like Orientalists from the First Gilded Age, Bowden had impressionistic fantasies of surrendering to primal forces. Ernest Renan (1823-1892) once attempted to define nationality subjectively as a dynamic, continuous process sustained by the ongoing will of its people to live together and affirm their shared identity. As soon as a people stops believing in itself, it ceases to exist. Similarly, Bowden was obsessed with the idea that a people can't survive with an anti-heroic myth about itself. Nations, however, are independent of belief insofar as they are situated and shared; they have origins and develop through space and time. In addition, there is a difference between nationality and nationalism; the latter is a doctrine about duties to a state. Bowden swaggers that the center can never hold, yet the center almost always holds. Every modern nation-state has minorities, just as every empire contains nations. Like Nietzsche, his doctrine faces a question of scale. To risk being master of the obvious, at a smaller scale, homogeneity is achieved at the expense of dominance; at a larger scale, the situation is reversed. Do you want the Shire or the Empire? A nation-state often attempts to paper over internal differences with myth—this is also Nietzschean and neo-conservative. Change imposes the same trade-offs. If we want dynamism, then much will be left behind in the past; if we select stasis, possibilities will be unrealized. There is a lack of sobriety in Bowden’s philosophy that avoids choices. Bowden liked the idea that everything contains everything else and conditions everything else; he believed in discrimination, but he placed himself in a fog of make-believe by equating impersonality with syphilis.

Bowden never attained escape velocity from the raised consciousnesses of the Baby Boomers. Boomers tend to be Romantics, albeit eclectic Romanticists. They’re believers. Their popular music is Meist, with holy choirs and organs occasionally appearing in the background of songs about sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll, as if there is something sacred about Self. All ideas are wrong, a Boomer stereotypically and earnestly believes, except mine.

As a contrast, in the First Gilded Age, William James was indecision incarnate. Unlike Bowden, James could never wholly make up his mind. James’ Gilded Age embrace of All meant that all possibilities had to be kept open, no matter how remote. He never felt comfortable completely refuting any idea! And yet, there was a method in the agnosticism. James remarked,

The best claim that a college education can possibly make on your respect, the best thing it can aspire to accomplish for you is this: that it should help you to know a good man when you see him.

Bereft of skepticism, reactionaries continuously fall for cranks, conmen, criminals, cult leaders, and grifters. Then they act surprised that liberals find a way to put points on the board, even when the conservatives win. What explains this paradox? A liberal like William James can subject his beliefs to critique, analysis, and irony. A heroic conservative, in contrast, not only follows deluded people but also deludes himself.

The Final Interview (Second Attempt)

JB: I’m beginning to doubt you’re Jonathan Bowden, even the undead version.

?: …Gubbahshuh…teeeear …doowwwwn

JB: Zombie Reagan? wtf

?: ..Bonzuuuuuh … buuuuunhzo

JB: No, I’m not Bonzo. Mr. President, why are you holding a rubber Trump mask?

Hegel, Escapism, and the Frankfurt School

Counter-Enlightenment perspectives did not last long because Hegel, the modern Heraclitus, absorbed them into his philosophy by uniting liberalism with progressivism. Liberalism subsequently was no longer about change but change that we can believe in. That which gains traction with reality is its own justification; reality has a liberal bias in that whatever combines instinct with practice wins out over that which does not. The end of history is rational self-consciousness in freedom.

Bowden believed we created a modern world that is not what it could have been; the modern and that which preceded it do not need to be in opposition. This is also what sunk Hegel’s reputation after 1848 when reactionaries crushed liberal nationalists. Belief wasn’t enough; idealism, in both senses, was superseded by realism. Liberals became more interested in economics, sociology, and the physical sciences. Meanwhile, modernism was soon born in the philosophy and creations of Richard Wagner, which affirmed that man was his own redeemer and placed him on a mythological horizon. This occurred during an era of increasing nationalism and imperialism. The Frankfurt School asked: is Wagner bourgeois? Does Wagner’s craft, like the music of John Williams today, have the spirit of an advertisement? Does this mode of art enchant life in ways that ought not to be mystified? In an age of mass-produced culture, should we be satisfied with what merely entertains, or should we expect art to say something? And, if so, should it say something true?

Conservative film chuds like William Jordan (the Critical Drinker) and Gary Buechler (Nerdrotic) have consistently argued no; they believe escapism constitutes art’s highest goal. Bowden championed kitsch and pulp — the Shadow, Doc Savage, Judge Dredd, Conan the Barbarian, etc., and their modern descendants as outlets of repressed heroism. This aestheticization of life leads to the aestheticization of politics, a core element of conservatism. Walter Benjamin saw this in fascism; I see it in British conservatism, particularly in the father of historical fiction and the grandfather of all genre fiction: Sir Walter Scott. Scott is a now neglected Tory author, regarded as a giant in his own time, whose reputation unjustly never recovered from E.M. Forster’s critique in Aspects of the Novel. During the eighteenth century, art had a morally edifying purpose. But with Scott, a novel’s setting becomes interesting in its own right — attire, weapons, diction, dialect, food, drink, rituals, festivals, legal proceedings, class distinctions, landscapes, towns, ruins, folk songs, poetry, transportation, mercantile activity — and we’re no longer telling mere stories but world-building. Scott typically justified his populist approach with a letter at the novel's beginning to the Reverend Dr. Dryasdust. Scott wrote badly on purpose, breaking all of the rules of concision, yet made every sentence somehow sing like a skateboard stunt.

The most salient fact over the past two-hundred-and-fifty years — the one fact that conditions all of the other facts — has been the rise of capitalism. It is a system that mystifies success and personalizes failure; it is not an accident that mediocrities such as Jordan Peterson are promoted way beyond their ability. The Frankfurt School philosophers defended high art and argued that we shouldn’t put up with slop and mystification; we should be living the lives we want to live, now, here, on planet Earth, rather than seeking escapes like a drug addict seeking his next hit. Conservatives place an imaginative load upon politics that it cannot carry; politics is about mundane, prosaic, boring things like collecting taxes and filling potholes. Conservatives also obscure that much misery in post-scarcity conditions is a policy choice. Trillionaires are expensive.

A conservative, always complaining, always resentful, always a victim, loyal to ghostly orders that no longer exist (usually a version of yesterday’s liberalism), puts themself in a self-imposed cage, believing ills come from without. Do they apply Ockham’s razor and notice family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, and countrymen with different ideas, values, temperaments, backgrounds, and priorities? Nope. Instead, they conclude others must have been brainwashed or turned into zombies by omnipotent, externally malign forces. Secret villains in the hated present supposedly repress them and drain them of spontaneity and self-assertion — the Burkean complaint mentioned above. To break out of the cage (Orwell remains a disease of the conservative brain) we need increasing doses of freedumb. It is freedumb, and not freedom, since conservatives have a problem with others using that freedom in ways they disapprove. Well, how did it go so wrong?

Conservatives tell a magical story about Communism, which, while defeated, somehow returned in a poorly written plot, like Palpatine. Bowden, in particular, needs Communism since his philosophy lacks a coherent villain. He finds no difference in kind between liberalism and communism, only a difference in intensity. This is a willful mistake since liberalism differs from communism and conservatism in two aspects. First, liberalism is agonistic. It celebrates conflict, creativity, and initiative. Competition between interests replaces the family idea, the extended tribe, and the household writ large. Everyone is not going to always agree; liberalism builds this into its politics. Secondly, liberalism believes in liberty, that is, in being in charge of your life, even if that means putting some restrictions on the power of commerce and the state. It isn't amicable toward concentrated power, be it political, economic, or social.

It is noteworthy that Emerson (1803-1882), the father of American philosophy, was an idol of Nietzsche that, unlike other idols, he never turned on and smashed. Emerson taught how to be your own man in a world where hierarchy and community have collapsed; liberal democracy, while not a sufficient condition, is a necessary condition for self-realization. Bowden slurs over the difference between inequality as difference, which liberalism accepts, and inequality of power, which liberalism attempts to mitigate. Conservatives too often have what Fromm called “necrophilic” personalities, the attitude of broken slaves looking for a master or a Führer to tell them what to do; they have Renfeld’s servile energy from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Look at the way they align themselves with billionaires who, after announcing they’re going to replace us all with immigrants, tell the conservatives to “fuck your own face.” A philosophy that aims for unbridled self-assertion terminates in zero self-respect. Why does this happen?

Nietzschean Limits

“Life is about death.” — Bong Bowden, not me

Nietzsche, rejecting any philosophical ground, didn’t want eternal victory and repose but endless struggle for its own sake, abhorring static conditions. Bowden, giving into knee-jerk contrarianism, expressed anger toward post-structuralists who do not believe in essentialism. Well, those people also use his Nietzschean operating system. Identical. Nietzsche was not a partisan man; he celebrated struggle itself. Michel Foucault (1926-1984), as is well-known, liked to cash things out into power relations. Gilles Deleuze (1925-1992) argued Being is constantly in flux; identity emerges from processes of change, interaction, and difference. For Nietzscheans in the gender theory business like Kosofsky Sedgwick (1950-2009) and Judith Butler (1956-), identity inhabits contested sites of meaning, that is, discursive spaces where identity is performed within or against social norms. Conservatives who attack Marxism and Communism in this context entirely miss the target.

Boomers had, as the song goes, sympathy with the devil. Is there such a thing as an optimistic Satanism? Satanism with a happy ending? Bowden liked to say his Nietzscheanism is essential or somehow primordial while that of others is merely destructive, but such words do not specify in what such a difference consists. Nietzsche, a pessimist like Schopenhauer, described his own pessimism as a pessimism of strength. Life is not all for the best. I can understand a Nietzschean who believes that since we all have to die, we ought to burn brightly. Bowden’s philosophy is wrecked on its own principles by the existence of other Nietzscheans who also believe a good war makes sacred any cause. This includes Nietzscheans into idpol stuff who are unscrupulous about using underhanded means, including violence, to impose their perspectives upon others.

Kitsch resembles pornography. It is an attempt to get emotions without paying for them. It blanks out consciousness with appetite; it is an attitude of feeding, not giving. Modern conservatism, from Carl Benjamin to Jared Taylor to Matt Walsh to Donald Trump, is based upon the power of belief. People have the wrong ideas and values, and we just need to replace them with the right ideas and values. This is just as sentimental as Hollywood films that believe that love conquers all, that you should always follow your dream, that we’re all the same underneath, and that good guys win.

Life requires sacrifice. Something must suffer so that something else may live. This is why the Christians saw the crucifixion as the central pivot of creation. They envisioned the universe as created, and creativity involves sacrifice since, given a blank canvas, an infinity of other choices are excluded, some better, some worse, so that one particular choice may exist. This made a Christian marriage sacred, a sacrifice, and a sacrament.

Nietzsche preferred Bizet’s Carmen over Wagner’s Parsifal because he rejected the Wagnerian idea of redemption through love and sacrifice. Nietzsche, a prophet of mass popular music, felt simple, catchy, easily understandable melodies as vehicles of vitality, even if it is the self-destructive vitality of a squanderer, and explicitly approved of the Africanization of the European spirit. (Nietzsche also writes someplace about the courage to have bad taste.) Those in the modernist shadow of Wagner faced a bigger problem: can Wagner’s magic falsify reality without falsifying itself? Those defending European high art faced an impasse. Consider the subject matter of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron. This meta-opera grappled intensely with the legacy of Parsifal by refusing to make graven images and materialize the sacred. The effort was perhaps unfinishable in principle, and its lack of completeness leaves questions about the relationship between art, religion, and civilization unresolved.

Music

In the novel Fight Club, it is asked, “If you could be either God's worst enemy or nothing, which would you choose?” This is the essence of GenX edgelordism. Bowden was both something of a GenXer, taking the Devil’s side in a metaphysical sense, and a Boomer, believing his beliefs without irony, cynicism, or even detachment. What he’s doing is not, strictly speaking, modernism. The first wave of modernists wanted to blast us away from reusing preexisting materials from our Christian and Greco-Roman inheritance; they were often Utopian and always individualist. The second generation included blackpillers who experienced WWI as a rupture and felt that everything needed to be torn down and rebuilt on new principles. The final generation, the patriot generation, believed in a willed Romantic modernism. None of this is a flight from religion into subjectivity; modernists aimed to protect the higher things from mass culture by making them difficult, even the religionists. (Stravinsky was devoutly Orthodox; Messiaen was devoutly Catholic. Such examples can be multiplied endlessly.)

What has changed? Postmodernity chopped everything up into external repeatable units. In science, a hundred years ago, it was easy for a mediocre physicist to do outstanding work; now, it is difficult for an outstanding physicist to do mediocre work. Sequels, reboots, remakes — the problem of originality infects everything. Most facts are accessible, such as the specific heat of water being 4.186 J/g°C. In the social critic Daniel Boortsin’s time in the mid-1900s, there were not enough original people or happenings to justify the vast appetite for them; the internet has exponentially increased the noise. There are takes upon takes upon takes, takes upon events that might happen, or events that never happened, or takes upon someone else’s take on someone else’s take. Sometimes, we get hot takes. People might believe things are as they seem, but ackchyually, we need to consider seriously the possibility that Adolf Hitler may have been an avatar of Vishnu. We’ve built an ecosystem that selects for attention-getting cranks.

Bowden’s philosophy has a plot — rebirth — with a modernist inversion. Bowden, like Nietzsche and Sade, was a misotheist. He wants us to become alive by becoming dead. This is not merely perversion or corruption but also an answer to one of the most profound questions. What is the meaning of suffering? Why is there suffering rather than nothing? In Sade’s case, the answer had a mechanistic form. If reality consists of atoms and void and nothing else, we are only real insofar as particles collide with each other. Other views are regarded as a delusion. And, to avoid desensitization, one must increase the dosage of shock, whether it be pain or pleasure. Pain, illness, suffering, decay, are not only morally good, but primordial and divine. It is dissolute, both self-assertive and self-destructive. Its anti-Platonism celebrates the triumph of matter over consciousness. It is the mentality of someone reduced to demons, that is, background physical processes, like a gambling addict, an attention addict, a sex addict, a food addict, a work addict, a drug addict. The Nietzschean response to those not burning the candle at both ends: the leisured secretly envy workaholics, the knowledgeable envy the ignorant, the competent envy the hapless, the cunning envy the naive, the sober envy the addicted, the healthy cowardly fear becoming unfit, and the secure cowardly fear destitution. How convincing is this?

Bowden had a compulsion for the fierce, the visceral, the over-the-top, the surreal, that which is “percussively inegalitarian and elitist,” feeling that “the grotesque is the ultimate anti-bourgeois style,” including the “burlesque extremism” of horror. He mentioned in several places that Clytemnesta is one of the most significant characters of Western art, even the prototype of Lady Macbeth, and also goes to the source:

"Modernist art is also concerned with concepts like fury and power. Power instead of beauty, or power as beauty, and these aesthetics are not popular. They are elitist aesthetics, but they are elitist aesthetics of the modern world rather than the early-modern, the medieval, the feudal, or the ancient. And yet they have always existed in art. The depictions of the Gorgon’s head in ancient Greek sculpture are the realization of ugliness, the demonic, and the ferocious as a new type of transgressive beauty.” -- Western Civilization Bites Back (Kindle Locations 3183-3187). Counter-Currents Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Given these considerations, if you enjoy music, you already know there is only one appropriate selection: Christopher Rouse’s Gorgon. The Boomers will be generally remembered for their eclectic neo-Romanticism that used modernist materials synthetically to create Romantic effects, and Rouse is no exception. (I side with Perseus over the Gorgons.)